ARTEFACTS OF PREDICTION

2 December 2025 – Sunday 28 June 2026

Manchester Museum

From tarot cards and uranium glass to paper dresses and futuristic games, The Artefacts of Prediction: Imagining Tomorrow explores how people throughout the modern era have tried to glimpse, design, or control what comes next.

Throughout the twentieth century and into our own time, the future has been imagined through science and superstition, through data, design, and dreams. Each artefact in this exhibition captures a moment of speculation — a time when the future felt close enough to touch. Some visions proved strikingly accurate; others now seem strange or impossible. Yet together they reveal our shared desire to make sense of uncertainty and to give shape to what lies ahead.

Drawing on objects from science, fashion, design, and popular culture, the exhibition invites visitors of all ages to consider how ideas about tomorrow reflect the hopes, fears, and technologies of their time — and how our own predictions will one day become artefacts of the past.

ABOUT THE ARTEFACTS

The exhibition combines objects and commissioned art. Objects were loaned from private collections, the Churchill Archives Centre, and purchased for the project from around the world. Original art was produced by Daniela Sherer.

ARTEFACTS

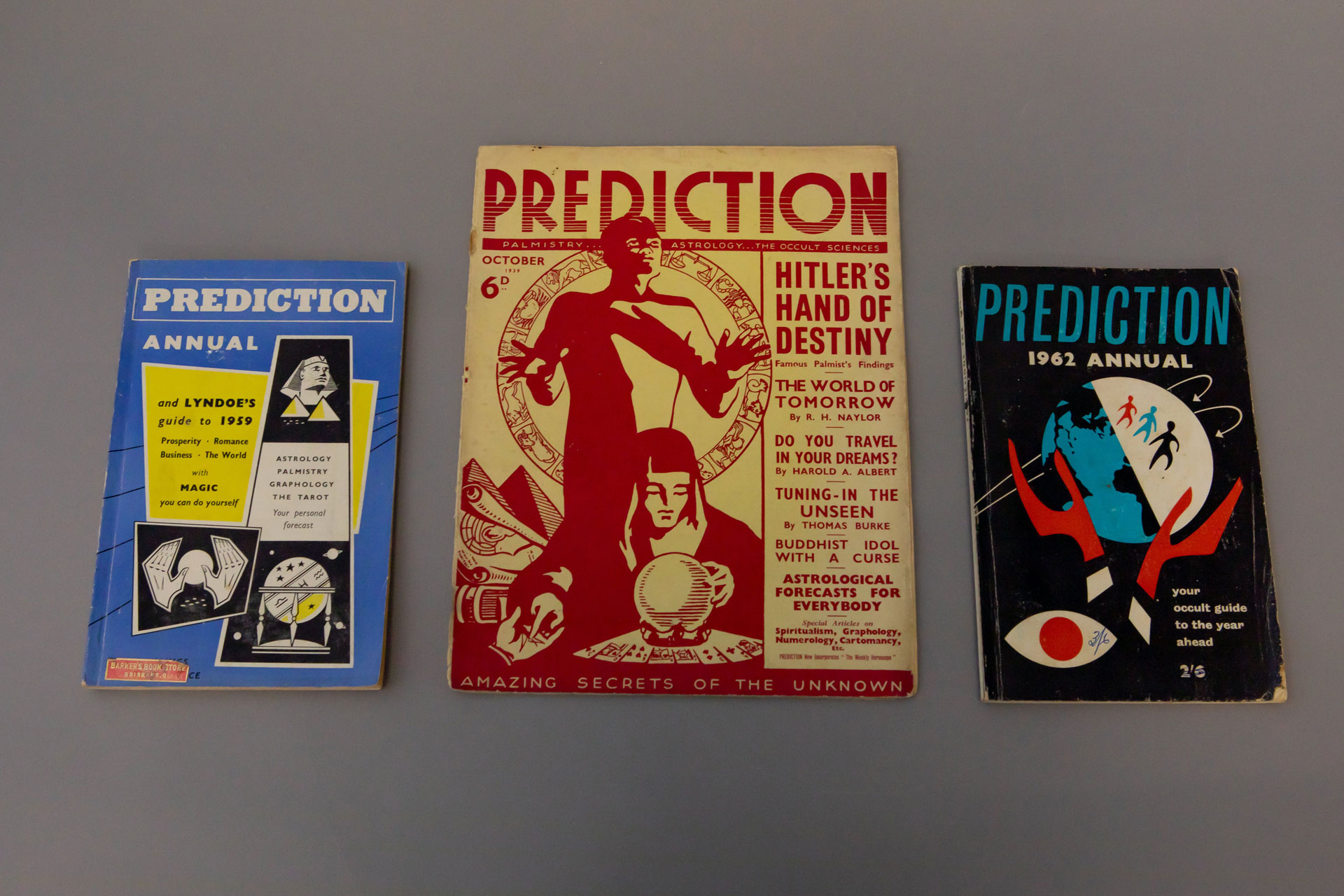

Prediction Magazine

1936–1950s

Launched in 1936, Prediction magazine promised to “publish the facts and theories of the various occult sciences” while remaining independent of any sect or movement. Its pages explored magic, astrology, telepathy, phrenology, yoga, and dream interpretation alongside psychology and personality theory. Advertisements offered spiritual guidance and astrological readings to help readers understand both the self and the unseen.

Reflecting the interwar fascination with mysticism and self-knowledge, Prediction connected the occult with emerging ideas of psychology and self-improvement. Its enduring appeal lay not in accurate forecasting but in its anticipation of modern obsessions with astrology, wellness, and the blending of science and spirituality. While mysticism remains popular, its focus has shifted—from reading global politics through an occult lens to seeking personal insight in a time of uncertainty.

Purchased with funds from the British Academy

Davidson Primrose Pearline Uranium Glass Plate

c. 1890–1900

This delicate plate is made of uranium glass, a material that glows with a soft green fluorescence under ultraviolet light. Uranium compounds were added to glass from the nineteenth century to produce a distinctive yellow-green tint. By the late Victorian period, manufacturers such as Davidson & Co. marketed these luminous wares as fashionable tableware under trade names like “Pearline.”

The Primrose Pearline plate reflects an age when scientific discovery and domestic life were closely intertwined. Its novelty captured the era’s fascination with progress, technology, and the unseen forces of nature. Yet the same element that made it glow with wonder—uranium—foreshadowed the atomic age’s mix of promise and peril. Once a parlour curiosity, it anticipated the twentieth century’s preoccupation with radiation, energy, and nuclear power: what Victorians saw as marvel, we now view with a blend of fascination and caution.

Purchased with funds from the British Academy

Uranium glass; manufacturer: Davidson & Co., Gateshead, England

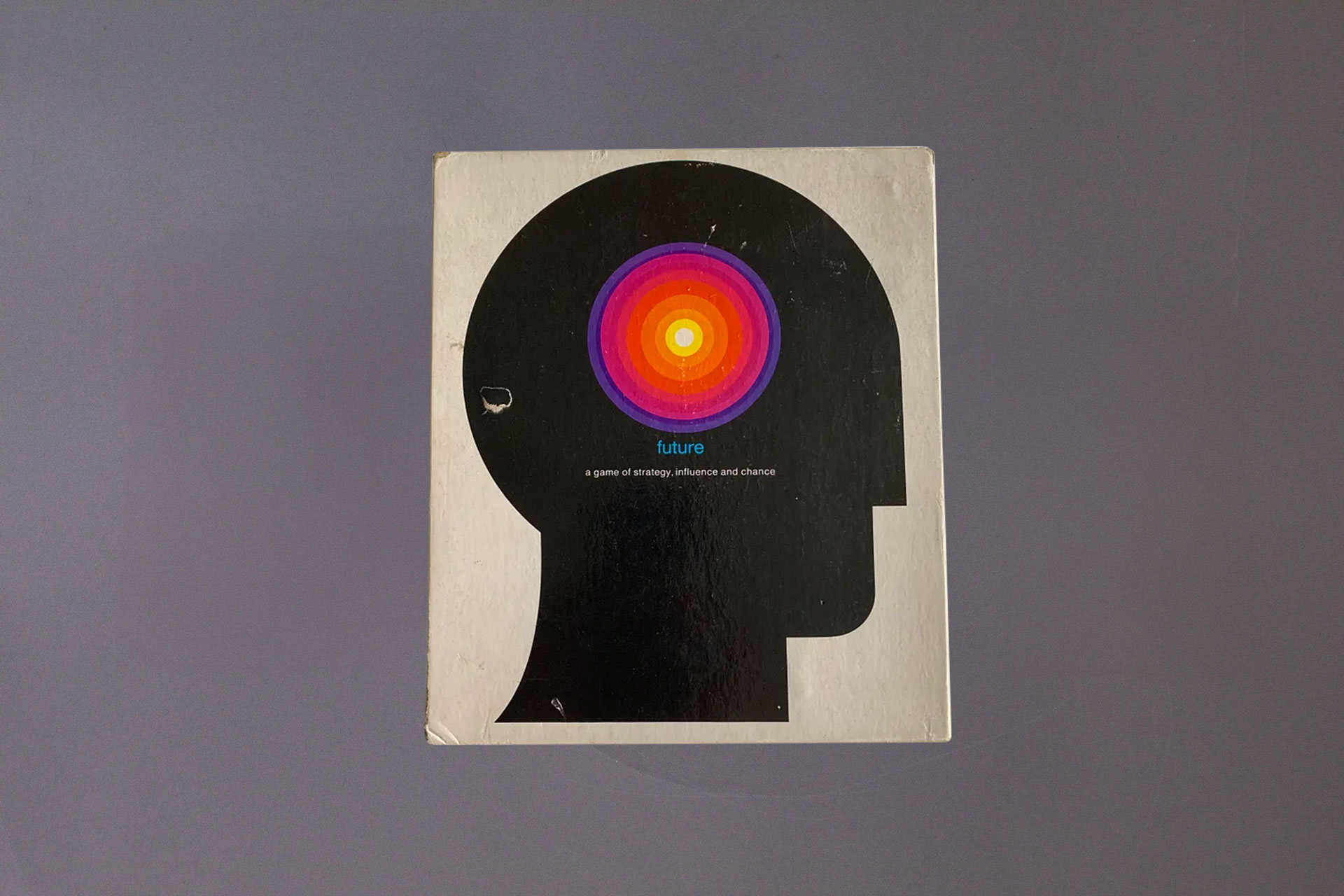

Future: A Game of Strategy, Influence and Chance

1966

This board game invited players to imagine and compete for control over the world to come. Combining elements of diplomacy, economics, and risk-taking, Future: A Game of Strategy, Influence and Chance reflected the anxieties and ambitions of the Cold War era, when technological innovation and political power seemed to determine humanity’s fate.

Marketed as both entertainment and education, Future turned global issues such as population growth, energy crises, and environmental change into manageable, rule-based play. Players navigated moral and strategic dilemmas that mirrored real-world debates about progress and responsibility. The game reflects the enduring human desire to turn uncertainty into strategy and imagination into action. Even when its forecasts missed the mark, its sense of possibility still feels alive today. Future reminds us that predicting tomorrow is never about precision alone — it is an act of creativity, collaboration, and belief in what might yet be possible.

Board game, ephemera, and accompanying period documents

Loaned from private collection of Scott Smith

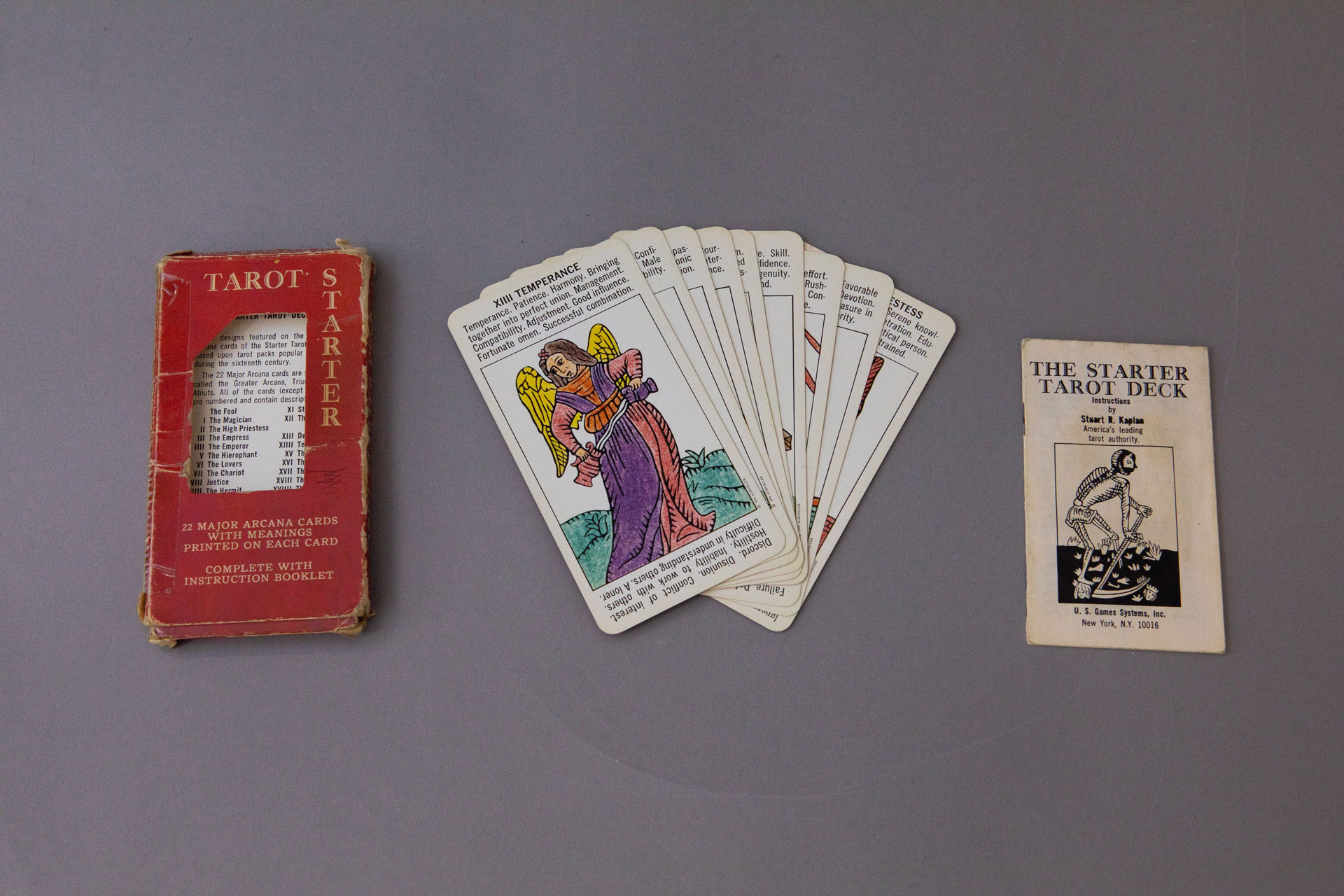

Deck of Tarot Cards

1977

This tarot card set, complete with printed instructions, represents a shift in twentieth-century divination practices. Emerging when the future felt increasingly uncertain, amid Cold War anxieties and the threat of nuclear annihilation, tarot reading offered individuals a way to regain a sense of control and meaning.

Rather than belonging solely to the realm of the occult, tarot sits between the rational and the irrational. It invites reflection on one’s own past and choices, while appealing to beliefs in destiny and unseen forces. The inclusion of instructions marked a move away from reliance on charismatic fortune-tellers toward a more democratic model: anyone could learn to read their own future. In this way, the deck mirrors a wider cultural turn toward self-knowledge and personal agency, blending mysticism with the emerging language of psychology and self-help.

Printed card; Starter Tarot Deck by Stuart R. Kaplan, U.S. Games Systems, New York

Each card 7 cm × 13 cm

Purchased with Funds from the British Academy

Spaceship

Daniela Shearer

2025

Spaceship is a short, animated film exploring humanity’s enduring fascination with predicting the future. Through dreamlike vignettes, from 19th-century fantasies of whale-drawn travel to mid-century visions of jetpacks, melting dishes, and underwater farms– the film reveals the many ways people have imagined what lies ahead. Each vision reflects the culture that created it as much as the future it foresaw.

Rather than making predictions, Spaceship invites viewers to reflect on the act of imagining the future: how our hopes, fears, and technologies shape what we think is possible. Some scenes feel eerily familiar, echoing concerns about perpetual war or computer domination, while others remain delightfully implausible. Together they celebrate the human impulse to dream, reminding us that every vision of tomorrow is a mirror of its own time.

Digital animation, hand-drawn and coloured

Digital display on 55-inch monitor (awaiting final projection specifications)

Commissioned for The Artefacts of Prediction Exhibition with funds from the British Academy

Bomb Shelter Designs

Ove Arup

1939

Engineer Ove Arup (1895-1988), born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne of Danish heritage, designed some of the most iconic buildings of the 20th century, including the Sydney Opera House. These drawings were created by Arup during the Second World War, when people in Britain faced threat of air raids. Arup designed strong, safe shelters to protect families and communities, using his skills to imagine what people would need in this scenario.

The drawings show how thinking about the future is not always about excitement or invention. Sometimes it is about planning for danger and helping people feel safer in uncertain times.

Technical drawing and artist sketch

Images licensed from Churchill Archives Centre, Courtesy of Arup

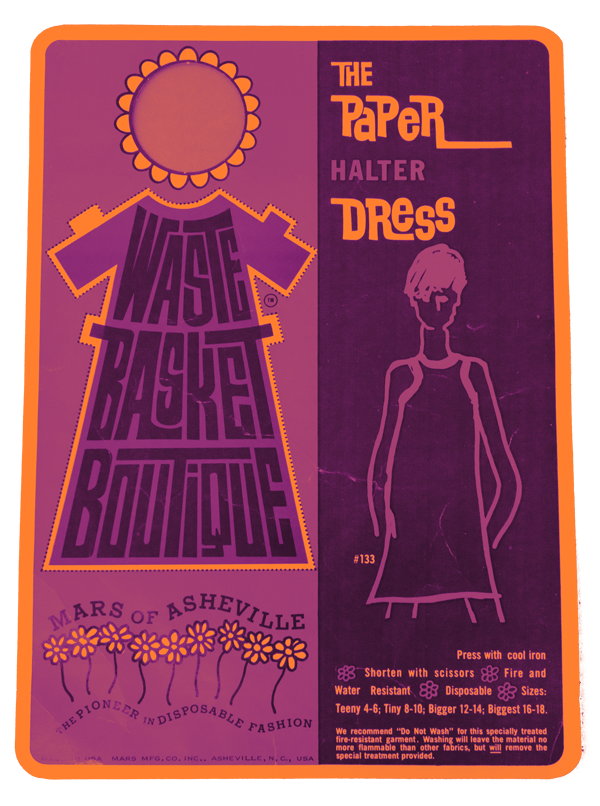

Wastebasket Boutique Paper Halter Dress

c. 1960–1970

This bold sleeveless halter dress, made from stiff bonded cellulose and printed with pop-inspired graphics, captures the spirit of 1960s disposable fashion. Designed in the mod shift style popularised by Mary Quant, it was part of a wave of industrial experimentation that transformed post-war consumer culture.

The paper dress symbolised freedom, novelty, and a new kind of accessibility in fashion. Cheap, customisable, and ephemeral, it anticipated today’s fast-fashion industry where trends move quickly, production is global, and clothing is designed to be replaced rather than repaired. At its best, the dress celebrated self-expression and spontaneity, allowing wearers to cut, tape, and restyle as they wished. Yet its disposability also revealed the costs of convenience. A brief fad that tore and creased easily, it foreshadowed a cycle of over-consumption that continues to challenge designers and consumers alike.

Bonded cellulose paper; manufacturer: Mars Hosiery, Asheville, North Carolina, USA

Dimensions to be confirmed

Purchased with Funds from the British Academy